CAN INDIA BE WORLD’S WORKSHOP?

Late last month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi kicked off his pet programme, Make In India, amid much fanfare. New Delhi’s Vigyan Bhavan, the venue of the launch, witnessed heads of top domestic and global companies nodding in approval as Mr Modi exhorted them to make India a manufacturing hub.

“You cannot attract investment just by an invitation. The most essential factor is trust. Let’s start with trust and the government will intervene only if it sees any deficiencies,” the prime minister added. He also unveiled the Make In India logo - a striding lion made of cogs, symbolising manufacturing - a portal to address queries of potential investors in 72 hours and identified 25 growth sectors to revive the manufacturing sector.

Business and industry captains listened in rapt attention as Mr Modi promised them a secure environment for their investments, a stable policy regime and easy and effective governance.

Manufacturing in doldrums A strong entrepreneurial culture, vast natural resources and a huge domestic market provide India the right ingredients to be a robust manufacturing hub. But contrary to the country’s inherent strengths and far removed from Mr Modi’s strong Make In India pitch, the manufacturing sector is in a bad shape. The little over Rs 15,00,000-crore sector contracted by 0.7 per cent in 2013-14 after expanding by a mere 1 per cent in 2012-13. Sadly, the sector remained subdued even during the country’s over 9 per cent economic growth period of 2005 to 2008, which was largely driven by the service sector.

The share of manufacturing in the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has stubbornly stuck around 15 per cent for almost three decades now. The number pales before China’s spectacular manufacturing strength, accounting for about 34 per cent of its GDP. In 1970, the Indian economy was larger than the Chinese economy. But today, China’s economy is thrice the size of India’s, and it is manufacturing that has made all the difference for the Asian giant.

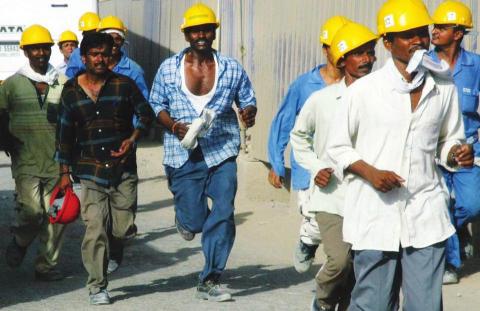

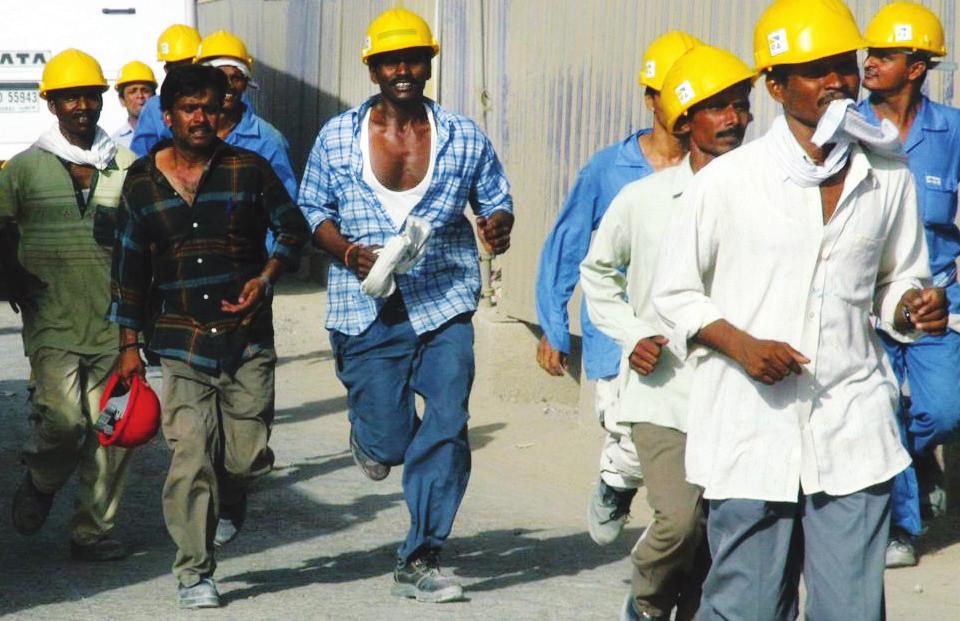

Incidentally, it is the poor state of manufacturing that is responsible for jobless growth in India. The country created 50 lakh manufacturing jobs between 2004-05 and 2011-12, the latest available official figures. During the same period, some 3.3 crore people left farms, looking for betterpaid work - an encouraging sign of economic development. But unfortunately, a majority of them were absorbed into the low-productive, irregular and low-paying unorganised sector, with manufacturing in a depressed state.

The country’s big dream of becoming the world’s workshop is shattered by harsh realities. Infrastructure bottlenecks and logistical challenges pose a big hurdle to the Make In India initiative. Poor roads, crumbling rail freight infrastructure, severe shortage of power and a lack of air connectivity to some remote, yet robust, manufacturing hubs have held back the country’s ambitious manufacturing plan. Besides, governance deficit and a skewed taxation policy have made India a very tough place to do business.

But perhaps the biggest hurdles to the country’s manufacturing ambitions are its archaic labour laws, new and complicated land acquisition law and tortuous environmental clearance regime.

Governance deficit, leading to redtapism and inordinate delay in getting clearances, has cost the economy dearly. No wonder, the country finds itself in an unenviable position in successive global Ease of Doing Business rankings. India slipped three positions to the 134th spot in the latest Ease of Doing Business ranking released by the World Bank this year. The list of 189 countries was topped by Singapore, with the other BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) nations - Russia at 92nd spot, China 96 and Brazil 116 - faring much better than India.

India is slotted in the third-lowest position in the same ranking, just above Bhutan and Afghanistan, within the South Asian region. The country cuts a sorry figure when it comes to its performance across sub indices of the Ease of Doing Business, such as starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity connection and the like. In the key parameter of starting a business, India finds itself in the embarrassingly low 179th position, with Russia, Brazil and China at the 88th, 123rd and 158th ranks respectively.

“You cannot attract investment just by an invitation. Let’s start with trust and the government will intervene only if it sees any deficiencies.”

Starting a new manufacturing venture in the country is quite a Herculean task. The new business will have to get more than 100 Central-, State- and local-level approvals ranging from registering a boiler or getting a fire department clearance to approval of construction activity and building

plan, getting a PAN, other tax identification numbers, clearances from pollution control board, chief inspector of factories and electricity board, among others. It typically takes six months to a year to clear all regulatory hurdles needed to build a new factory in the country.

The taxation policy too has taken its toll on the country’s manufacturing sector. Since liberalisation of the economy in 1991, the country’s Customs Duty has been lowered periodically. This has skewed the tax policy in favour of imports over local manufacturing. Besides, inconsistent tax policies have made foreign companies nervous about investment in India. The recent Union Budget did try to calm investors’ anxiety over tax policies. But these steps are far from enough to revive confidence among global players who look for a clearcut and stable tax policy. The long stalled Goods and Services Tax (GST) can actually go a long way in putting an end to the labyrinthine tax system that varies from State to State and compounds problems for investors.

Labour pain: The Indian labour market suffers from a curious mix of improbably stringent laws and totally lax implementation. It is highly distorted, thanks to a multiplicity of laws. Labour laws are a part of the Concurrent List, which means both the Central and State governments can legislate on labour. This has resulted in an overlapping jurisdiction with the industry and its employees at the mercy of nearly 200 Central and State labour laws.

The Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, is one such ancient law that has prevented India from becoming a manufacturing hub. One of its clauses states that all industrial units with over 100 employees will have to get the government’s permission to close down operations.

According to the Act, industrial disputes have to be settled through a maze of six agencies, making it almost impossible for employers to lay off workers or shut down factories.

According to the Act, industrial disputes have to be settled through a maze of six agencies, making it almost impossible for employers to lay off workers or shut down factories.

Most industries tend to keep their labour force as small as possible and desist from expanding the size and scale of their operations to escape onerous legal requirements. Besides, they have been heavily relying on contract labour. Ironically, the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970, which was initially designed to protect permanent employees, regulate widespread misuse of contract labour and uphold the rights of contract labourers, has done exactly the opposite of what it was enacted for.

The Act prohibits industries from engaging contract labourers in their core activities and stipulates minimum wages and basic working conditions for contract workers. But over the years, contradicting interpretations of the Act by successive governments and laxity on the part of authorities in implementing this law have led to widespread contractualisation of labour. With industries changing their contract labourers quite too often, they have been deprived of basic facilities and rightful compensation. This exploitation has often manifested in violent labour unrest, especially in automobile and auto component industries.

The contractual system of employment has come to occupy the core of Indian manufacturing today, accounting for about 58 per cent of the total organised sector. Such cumbersome labour laws have further shrunk the organised sector, which today makes up only 16 per cent of the total workforce of the country. Apart from stifling the manufacturing sector, these laws have destroyed the labour market and done precious little for workers’ welfare.

Not surprisingly, complex regulations have deeply hurt the Indian labour market, which has been ranked 99th by investment bank Morgan Stanley in labour market efficiency among 148 countries. China, Japan and the USA rank 34, 23 and 4 respectively in the same category. Meanwhile, labour productivity is low in India compared with that in China and other emerging markets. According to a McKinsey report, workers in India’s manufacturing sector are almost four to five times less productive than their counterparts in Thailand and China. Besides, shortage of skilled labour in the country, with only about 2 per cent of its total workforce

qualifying as skilled workers, impedes the country’s quest to emerge as a global manufacturing hub.

Green hurdles: As the government raises the stakes for manufacturing in the country, it will have to work hard on rationalising the existing environmental clearance process. About 253 major projects worth over Rs 12,00,000 crore are stuck in the country owing to a lack of green signal from the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF). According to official data, about 44 per cent of the stalled projects with investment over Rs 1,000 crore are held up for want of environment, forest and wildlife clearances from the MoEF.

The country’s green nod process is a mess, unable to strike a balance between demands of growth and the need to protect the environment. According to the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, about 39 projects are mandated to get environmental clearance (wildlife and forest clearances too if they are situated in or near a forest) to start operation. But this long-drawn process with its utter ar-bitrariness has slowed down approvals and clogged huge investments. The environmental clearance process is neither independent and nor based on science as it may appear. Besides, political considerations do often play a role in making or marring a project in the garb of green nod.

The arbitrariness is borne out by the fact that the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) notification, the vital document that guides the environmental approval process, has undergone changes more than 100 times in less than seven years of coming into force. As a result, contrary interpretations of the notification every few years have further muddled the process and delayed clearances. Moreover, the Expert Appraisal Committees (EACs), which assess the EIAs and recommend projects, have become a parking lot for retired bureaucrats.

The US and other developed countries have simplified the environmental approval process with clear-cut norms and vested authority in an independent expert body for appraising and approving projects. The mess in environmental clearance in India is a result of arbitrary procedures, ambiguous norms and concentration of policy-making and regulatory powers with the MoEF.

In January this year, the Supreme Court pulled up the MoEF for shoddy environmental clearance process and asked it to constitute an independent regulator to approve projects. However, there seems to be no progress on this front so far.

Land woes: Meanwhile, the new land acquisition law - The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 - has complicated matters for major projects looking to acquire land. The new Act, which replaced the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, enacted during the British rule, was framed to rid the flaws associated with the previous legislation, such as forced land acquisition.

The new Act has got its intentions right. It mandates a consent clause for the State to go ahead with land acquisition, requiring consent of 70 and 80 per cent of landowners for public-private partnership (PPP) and private projects respectively. It recommends payment of compensation for land losers up to four times the market value in rural areas and twice the market value in urban areas. The tragedy of the previous law was compensation based on circle rates, which are notorious for being outdated and not even remotely indicative of the actual rates prevailing in the area. The new law also deals with various forms of compensation, such as land for land, housing, employment and annuities.

This is also the first law that links land acquisition and the accompanying obligations for resettlement and rehabilitation. The Act directs States to impose limits on the area of agricultural land that can be acquired. It also stipulates a social impact assessment of every project that must be completed within six months.

Despite all its noble objectives, the new Act seems to have gone over boarding correcting the anomalies of the previous law. Industrialists and other project promoters are worried that the consent clause, huge compensation and social impact assessment for all projects, irrespective of the size, will lead to a further delay in projects going on stream, ultimately push up production cost and badly hit the country’s ambitious manufacturing growth plans. Many State revenue ministers, in their recent meeting with Rural Development Minister Nitin Gadkari, have urged for scrapping the consent clause for PPP projects, slashing it to 50 per cent for private projects and doing away with the mandatory social impact assess-ment clause for small projects.

Beyond rhetoric: Going by the sheer size and scale of the Make In India campaign, Mr Modi has certainly succeeded in packaging the manufacturing endeavour well. But the task ahead of reviving the sector is quite challenging. The government has made a good beginning in addressing the ticklish issues.

The first steps of overhauling the outdated labour laws have begun in right earnest. The government was quick to pluck the low-hanging fruits by getting amendments to the Apprentices Act, 1961, the Factories Act, 1948, and the Labour Laws (Exemption from Furnishing Returns and Maintaining Registers by Certain Establishments) Act, 1988, passed by the Parliament in its monsoon session. All these measures clearly enhance the welfare of workers and make it easier for industries to operate.

The prime minister has also unfurled the Skill India Mission to transform Indian workers into a highly skilled labour force.

Under the National Skill Development Corporation, the government is giving a big push to promote skill development through the PPP mode. Besides, a separate Skill Development Ministry in the Modi government speaks volumes about the government’s commitment in this direction.

Yet there is a long way to go for India to become a manufacturing hub. The contentious labour laws, like the Industrial Disputes Act and the Contract Labour Act, need to be over-hauled. Besides, there is an urgent need to streamline the environmental clearance regime and rationalise the new land acquisition Act. The prime minister has set an ambitious target of improving the country’s Ease of Doing Business ranking to 50 from the current 134. This will require simplifying a number of long-winding procedures for starting ventures.

Meanwhile, experts estimate that the country will have to create nearly 10 crore jobs in the next decade - 1 crore every year - to absorb the additional manpower entering the labour market. According to official estimates, about 20 per cent of Indian youth is currently unemployed. Add to this, the additional workforce each year, and it will lead to a huge pool of unemployed or underemployed human resource.

A robust manufacturing sector can easily absorb this manpower. Besides, it can lead to a virtuous cycle of skilling, employing and empowering a large section of the country’s population and also trigger broad-based economic growth. However, the country’s service sector-led model, which is capital-rather than labour intensive, has resulted in lopsided growth. It has provided ample job opportunities for skilled employees but left out a vast pool of unskilled labourers to fend for themselves in the unorganised sector.

The Make In India campaign makes a welcome attempt to revitalise manufacturing and widen economic growth. It is essentially an attractively packaged extension of the National Manufacturing Policy of 2011. The policy aims at enhancing the share of manufacturing in GDP to 25 per cent from the current 15 per cent and creating 10 crore jobs in the sector by 2025. It envisions setting up of national investment and manufacturing zones (NIMZs) for building the country’s manufacturing muscle.

In fact, long before the NIMZs, there were special economic zones (SEZs), which were planned as vibrant manufacturing enclaves that doubled up as export hubs. However, SEZs today are in a moribund state, thanks to inherent policy issues and the same challenges that have affected the manufacturing sector. The muchtouted NIMZs too have been impacted by the same issues and failed to take off. The Modi government should go beyond catchy slogans and impressive targets and start addressing the real issues. Only then can Make In India transform into Made In India.

BUDDING MANAGERS

OCTOBER 2014 ISSUE

Add new comment